The orange sky got more attention, but the relentless blue skies of October might portend longer-term consequences.

San Francisco has weather records stretching back to 1850. Only once in that time period has the city recorded 0.01 inches of rain or less back-to-back in the month of October, in 1965-1967, according to rainfall records kept by Jan Null of Golden Gate Weather. We’ve just tied that record. Downtown San Francisco recorded 0.01 inches of rain in October 2019 and again in October 2020; the weather station at the San Francisco airport, and several other stations around the Bay Area, have registered 0.00 back-to-back, according to the National Weather Service.

Though the monthly average is just over 1 inch, October is a highly variable month, and it’s not unusual to end the month with little or no rain in the Bay Area. It is however exceptionally bad timing to do it twice in a row for only the second time in the last 170 years, as the state reels from fires, heat and smoke, on the heels of a record-breaking dry winter and as most forecasts call for a drier than normal winter ahead. And while there is an element of misfortune to this dry streak, University of Texas climate scientist Geeta Persad said climate change is also loading the dice, making extremely dry seasons and back-to-back dry autumns more probable.

“Yes, absolutely we’ll have glorious years in the future,” she said. “But when we think about the resilience our system has right now, we saw in the 2012-2016 drought it really only took the first two years for California to decide to pass the most comprehensive groundwater management law that had ever passed in California. It doesn’t take many years of bad conditions where that type of transformative change is necessary.”

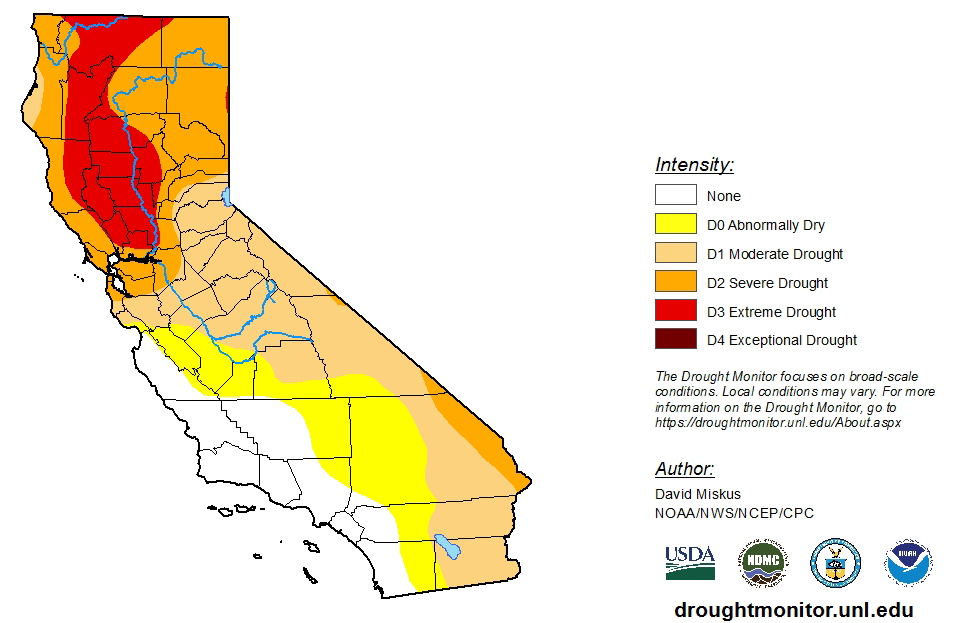

Federal drought monitor map of California as of October 29, 2020. (Map by David Miskus, NOAA / NWS / NCEP / CPC)Persad was the lead author on a paper in the journal Climatic Change in March 2020 that used fine-scale models to look at how and when water is likely to fall in California in the future, and what that means for water supply. The paper found that management is based largely on overly broad models and outdated patterns that don’t reflect the extremes headed our way. While water managers might appear prepared for variability because rain and snow in California has always been variable, Persad said future wet and dry swings are going to be more extreme than anything we’ve seen before.

Climate models show the timing and delivery of California precipitation shifting dramatically, with more very dry years, more water expected as rain as the climate warms, and more of it falling in the core winter months in massive superstorms. As a consequence reservoirs built to slowly capture water from snow might now lose water too rapidly in the heat, while rapidly overtopping and posing flood risks when the rain does fall. Evenly distributed rain that falls gradually over a six-month rainy season recharges groundwater in a way that all that rain falling in a handful of superstorms doesn’t.

“We’re used to having swings between dry and wet periods,” Persad said. “We know we have a dry season and wet season. The population of the West Coast knows more about the phrase El Niño than people in the rest of the country. But just because we’ve had experience with those swings in the past does not mean we’re prepared for the kinds of swings in the future.”

While it’s still too early to say what this winter will look like, most long-term projections call for it to be drier than average on the West Coast. Almost all of Northern California is already in severe or extreme drought, according to the federal drought monitor. And a dry winter this year could mean even more challenges for already stressed ecosystems and the people who rely on them.

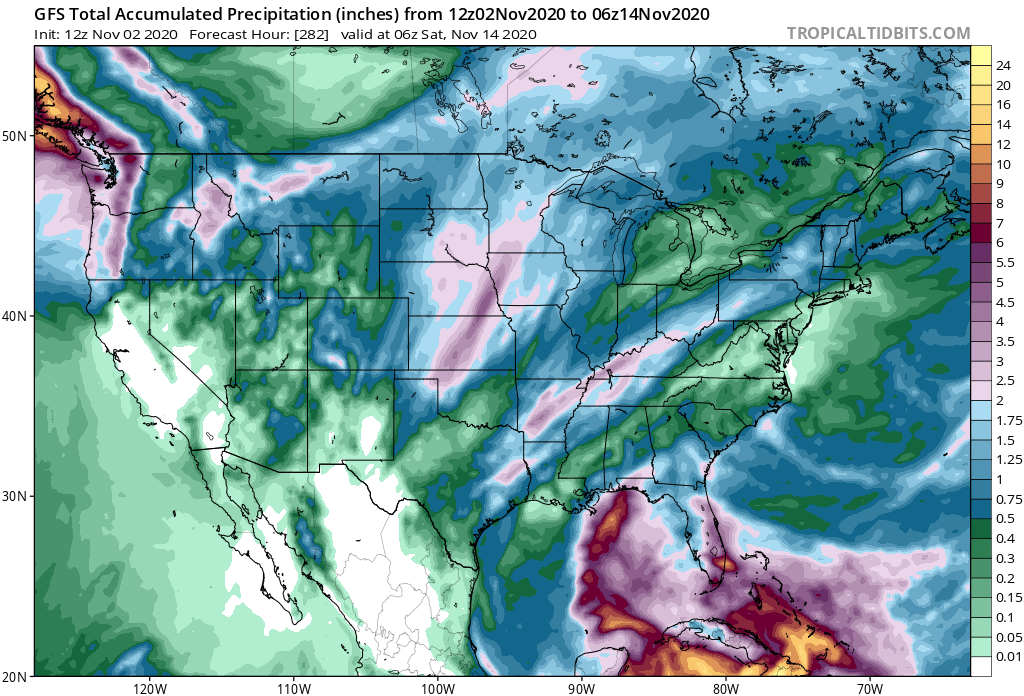

The National Centers for Environmental Prediction GFS model shows rain everywhere in the country except central California through November 14. (Image courtesy Tropical Tidbits)Larger water systems will likely be fine this year, said Texas A&M postdoctoral research associate Amanda Fencl, who wrote her dissertation on California water management during the 2012-2016 drought. Most major water systems have 3-to-5-year drought plans, Fencl said, and at this point they’ll mainly be just watching to see what unfolds this winter. As of November 1 the state’s reservoirs are mostly between 70-100 percent of their average historic capacity.

“Most systems feel comfortable being able to weather a 3-5 year drought at this point, especially with the few wet seasons we’ve had,” Fencl said. “It’s really only year two that systems start to get extra nervous about whether drought is going to persist or not.”

But smaller systems are more vulnerable more quickly, she said. That’s especially true in the Central Valley, where Union of Concerned Scientists western states climate scientist Jose Pablo Ortiz Partida said one million people already don’t have reliable access to drinking water.

Wells throughout the San Joaquin Valley went dry in the last drought and haven’t recharged. Pacific Institute research associate Darcy Bostic said that in many communities that rely on wells, people are still drinking from interim tanks in their yards. And Ortiz added that it’s not just water quantity but quality that’s lacking — farmworkers often irrigate agricultural fields with water that’s cleaner than what’s in their wells at home.

“It’s not only what is happening, but what already happened,” Ortiz said. “We’ve been mining our aquifers, mainly for agriculture. It’s like a bank account. We were lucky to start with a very high balance, but for many years we’ve been taking way more than the water that comes in and naturally recharges. It’s already a problem, particularly in some places in the Central Valley. But it will definitely become a bigger problem in the future in California.”

Want even more stories about Bay Area nature? Sign up for our weekly newsletter!

Fencl said that algal blooms in 2015 made it hard for water agencies to treat even the water coming out of reservoirs, and that no matter the size of the agency, in the peak of the drought their plans weren’t sufficient for the impacts that arrived. She said she hopes this time around that relationships and blueprints developed in that crisis will make navigating this one easier. It’s a “window of opportunity for innovation,” she said, and the state could help by funding capital projects.

“It’s to the state’s collective benefit to think about what kind of infrastructure lift is needed so we’re not drilling deeper wells during a drought,” Fencl said. “[Now is the time to] think about water alternatives so they’re not having to create technical solutions in the middle of a crisis.”

Bostic agreed: the state should start preparing now.

“The state never has to wait for the drought to begin,” she said. “So much of what I hope happens, happens before drought.”

November 03, 2020 at 05:12AM

https://baynature.org/2020/11/02/after-another-dry-october-has-the-drought-returned/

After Another Dry October in the Bay Area, Is Drought Back? - Bay Nature

https://news.google.com/search?q=dry&hl=en-US&gl=US&ceid=US:en

No comments:

Post a Comment